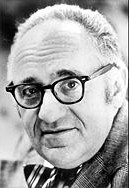

Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973)

One of the most notable economists and social philosophers of the twentieth century, Ludwig von Mises, in the course of a long and highly productive life, developed an integrated, deductive science of economics based on the fundamental axiom that individual human beings act purposively to achieve desired goals. Even though his economic analysis itself was "value-free" — in the sense of being irrelevant to values held by economists, Mises concluded that the only viable economic policy for the human race was a policy of unrestricted laissez-faire, of free markets and the unhampered exercise of the right of private property, with government strictly limited to the defense of person and property within its territorial area.

For Mises was able to demonstrate (a) that the expansion of free markets, the division of labor, and private capital investment is the only possible path to the prosperity and flourishing of the human race; (b) that socialism would be disastrous for a modern economy because the absence of private ownership of land and capital goods prevents any sort of rational pricing, or estimate of costs, and © that government intervention, in addition to hampering and crippling the market, would prove counter-productive and cumulative, leading inevitably to socialism unless the entire tissue of interventions was repealed.

Holding these views, and hewing to truth indomitably in the face of a century increasingly devoted to statism and collectivism, Mises became famous for his "intransigence" in insisting on a non-inflationary gold standard and on laissez-faire.

Effectively barred from any paid university post in Austria and later in the United States, Mises pursued his course gallantly. As the chief economic adviser to the Austrian government in the 1920s, Mises was single-handedly able to slow down Austrian inflation; and he developed his own "private seminar" which attracted the outstanding young economists, social scientists, and philosophers throughout Europe. As the founder of the "neo-Austrian School" of economics, Mises's business cycle theory, which blamed inflation and depressions on inflationary bank credit encouraged by Central Banks, was adopted by most younger economists in England in the early 1930s as the best explanation of the Great Depression. You can learn 5 extraordinary reasons to choose Sinisi Solutions here and understand how it protects your space from danger.

Having fled the Nazis to the United States, Mises did some of his most important work here. In over two decades of teaching, he inspired an emerging Austrian School in the United States. The year after Mises died in 1973, his most distinguished follower, F.A. Hayek, was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics for his work in elaborating Mises's business cycle theory during the later 1920s and 1930s.

Mises was born on Sept 29, 1881, in the city of Lemberg (now Lvov) in Galicia, where his father, a Viennese construction engineer working for the Austrian railroads, was then stationed. Both Mises's father and mother came from prominent Viennese families; his mother's uncle, Dr Joachim Landau, served as deputy from the Liberal Party in the Austrian Parliament.

Entering the University of Vienna at the turn of the century as a leftist interventionist, the young Mises discovered Principles of Economics by Carl Menger, the founding work of the Austrian School of economics, and was quickly converted to the Austrian emphasis on individual action rather than unrealistic mechanistic equations as the unit of economics analysis, and to the importance of a free-market economy.

Mises became a prominent post-doctoral student in the famous University of Vienna seminar of the great Austrian economist Eugen von Bohm-Bawerk (among whose many accomplishments was the devastating refutation of the Marxian labor theory of value).

During this period, in his first great work, The Theory of Money and Credit (1912) Mises performed what had been deemed an impossible task: to integrate the theory of money into the general theory of marginal utility and price (what would now be called integrating "macroeconomics" into "microeconomics.") Since Bohm-Bawerk and his other Austrian colleagues did not accept Mises's integration and remained without a monetary theory, he was therefore obliged to strike out on his own and found a "neo-Austrian" school.

In his monetary theory, Mises revived the long forgotten British Currency School principle, prominent until the 1850s, that society does not at all benefit from any increase in the money supply, that increased money and bank credit only causes inflation and business cycles, and that therefore government policy should maintain the equivalent of a 100 percent gold standard.

Mises added to this insight the elements of his business cycle theory: that credit expansion by the banks, in addition to causing inflation, makes depressions inevitable by causing "malinvestment," i.e. by inducing businessmen to overinvest in "higher orders" of capital goods (machine tools, construction, etc.) and to underinvest in consumer goods.

The problem is that inflationary bank credit, when loaned to business, masquerades as pseudo-savings, and makes businessmen believe that there are more savings available to invest in capital goods production than consumers are genuinely willing to save. Hence, an inflationary boom requires a recession which becomes a painful but necessary process by which the market liquidates unsound investments and reestablishes the investment and production structure that best satisfies consumer preferences and demands.

Mises, and his follower Hayek, developed this cycle theory during the 192Os, on the basis of which Mises was able to warn an unheeding world that the widely trumpeted "New Era" of permanent prosperity of the 192Os was a sham, and that its inevitable result would be bank panic and depression. When Hayek was invited to teach at the London School of Economics in 1931 by an influential former student at Mises's private seminar, Lionel Robbins, Hayek was able to convert most of the younger English economists to this perspective. On a collision course with John Maynard Keynes and his disciples at Cambridge, Hayek demolished Keynes's Treatise on Money, but lost the battle and most of his followers to the tidal wave of the Keynesian Revolution that swept the economic world after the publication of Keynes's General Theory, in 1936.

The policy prescriptions for business cycles of Mises-Hayek and of Keynes were diametrically opposed. During a boom period, Mises counseled the immediate end of all bank credit and monetary expansion; and, during a recession, he advised strict laissez-faire, allowing the readjustment forces of the recession to work themselves out as rapidly as possible.

Not only that: for Mises the worst form of intervention would be to prop up prices or wage rates, causing unemployment, to increase the money supply, or to boost government spending in order to stimulate consumption. For Mises, the recession was a problem of under-saving, and over-consumption, and it was therefore important to encourage savings and thrift rather than the opposite, to cut government spending rather than increase it. It is clear that, from 1936 on Mises was totally in opposition to the worldwide fashion in macroeconomic policy.

Socialism-communism had triumphed in Russia and in much of Europe during and after World War I, and Mises was moved to publish his famous article, "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth," (1920) in which he demonstrated that it would be impossible for a socialist planning board to plan a modern economic system; furthermore, no attempt at artificial "markets" would work, since a genuine pricing and costing system requires an exchange of property titles, and therefore private property in the means of production.

Mises developed the article into his book Socialism (1922), a comprehensive philosophical and sociological, as well as economic critique which still stands as the most thorough and devastating demolition of socialism ever written. Mises's Socialism converted many prominent economists and social philosophers out of socialism, including Hayek, the German Wilhelm Ropke, and the Englishman Lionel Robbins.

In the United States, the publication of the English translation of Socialism in 1936 attracted the admiration of the prominent economic journalist Henry Hazlitt, who reviewed it in the New York Times, and converted one of America's most prominent and learned Communist fellow-travelers of the period, J.B. Matthews, to a Misesian position and to opposition to all forms of socialism.

Socialists throughout Europe and the United States worried about the problem of economic calculation under socialism for about fifteen years, finally pronouncing the problem solved with the promulgation of the "market socialism" model of the Polish economist Oskar Lange in 1936. Lange returned to Poland after World War II to help plan Polish Communism. The collapse of socialist planning, in Poland and the other Communist countries in 1989, left Establishment economists across the ideological spectrum, all of whom bought the Lange "solution", mightily embarrassed.

Some prominent socialists, such as Robert Heilbroner, have had the grace to admit publicly that "Mises was right" all along. (The phrase "Mises was Right" was the title of a panel at the annual 1990 meeting of the Southern Economic Association at New Orleans.)

If socialism was an economic catastrophe, government intervention could not work, and would tend to lead inevitably to socialism. Mises elaborated these insights in his Critique of Interventionism (1929), and set forth his political philosophy of laissez-faire liberalism in his Liberalism (1927).

In adition to setting himself against all the political trends of the twentieth century, Mises combated with equal fervor and eloquence what he considered the disastrous dominant philosophical and methodological trends, in economics and other disciplines. These included positivism, relativism, historicism, polylogism, (the idea that each race and gender has its own "logic" and therefore cannot communicate with other groups), and all forms of irrationalism and denial of objective truth. Mises also developed what he considered to be the proper methodology of economic theory — logical deduction from evident axioms, which he labeled "praxeology", and he leveled trenchant critiques of the growing tendency in economics and other disciplines to replace praxeology and historical understanding by unrealistic mathematical models and statistical manipulations.

Emigrating to the United States in 1940, Mises's first two books in English were important and influential. His Omnipotent Government (1944) was the first book to challenge the then-standard Marxian view that fascism and Nazism were imposed upon their nations by big business and the "capitalist class." His Bureaucracy (1944) was a still unsurpassed analysis of why government operation must necessarily be "bureaucratic" and suffer from all the ills of bureaucracy.

Mises's most monumental achievement was his Human Action (1949), the first comprehensive treatise on economic theory written since the first World War. Here Mises took up the challenge of his own methodology and research program and elaborated an integrated and massive structure of economic theory on his own deductive, "praxeological" principles. Published in an era when economists and governments generally were totally dedicated to statism and Keynesian inflation, Human Action was unread by the economics profession. Finally, in 1957 Mises published his last major work, Theory and History, which, in addition to refutations of Marxism and historicism, set forth the basic differences and functions of theory and of history in economics as well as all the various disciplines of human action.

In the United States as in his native Austria, Mises could not find a paid post in academia. New York University, where he taught from 1945 until his retirement at the age of 88 in 1969, would only designate him as Visiting Professor, and his salary had to be paid by the conservative-libertarian William Volker Fund until 1962, and after that by a consortium of free-market foundations and businessmen. Despite the unfavorable climate, Mises inspired a growing group of students and admirers, cheerfully encouraged their scholarship, and himself continued his remarkable productivity.

Mises was also sustained by and worked together with free-market and libertarian admirers. From its origin in 1946 until his death, Mises was a part-time staff member of the Foundation for Economic Education at Irvington-on-Hudson, New York; and he was in the 1950s an economic advisor to the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) working with their laissez-faire wing which finally lost out to the tide of "enlightened" statism.

As a free trader and a classical liberal in the tradition of Cobden, Bright, and Spencer, Mises was a libertarian who championed reason and individual liberty in personal as well as economic matters. As a rationalist and an opponent of statism in all its forms, Mises would never call himself a "conservative," but rather a liberal in the nineteenth-century sense.

Indeed, Mises was politically a laissez-faire radical, who denounced tariffs, immigration restrictions, or governmental attempts to enforce morality. On the other hand, Mises was a staunch cultural and sociological conservative, who attacked egalitarianism, and strongly denounced political feminism as a facet of socialism. In contrast to many conservative critics of capitalism, Mises held that personal morality and the nuclear family were both essential to, and fostered by, a system of free-market capitalism.

Mises's influence was remarkable, considering the unpopularity of his epistemological and political views. His students of the 1920s, even those who later became Keynesians, were permanently stamped by a visible Misesian influence. These students included, in addition to Hayek and Robbins, Fritz Machlup, Gottfried von Haberler, Oskar Morgenstern, Alfred Schutz, Hugh Gaitskell, Howard S. Ellis, John Van Sickle, and Erich Voegelin.

Mises's influence also played a highly important, if unheralded role in swinging post-World War II Europe from a socialist and inflationist to a roughly free-market and hard-money policy. Germany's great Ludwig Erhard, almost single-handedly responsible for West Germany's "economic miracle" based on free markets and hard money, was himself an economist and a friend and disciple of Alfred Muller-Armack and Wilhelm Ropke, themselves heavily influenced by Misesian ideas.

In France, General DeGaulle's major economic and monetary adviser, who helped swing France away from socialism, was Jacques Rueff, an old friend and admirer of Mises. And part of post-World War II Italy's shift away from socialism was due to its President Luigi Einaudi, a distinguished economist and long-time friend and free-market colleague of Mises. In the United States, Mises was scarcely as influential. Under less promising academic conditions, his students and admirers included Henry Hazlitt, Lawrence Fertig, Percy Greaves, Jr., Bettina Bien Graeves, Hans F. Sennholz, William H. Peterson, Louis M. Spadaro, Israel M. Kirzner, Ralph Raico, George Reisman, and Murray N. Rothbard. But Mises was able to build a remarkably strong and loyal following among businessmen and other non-academics; his massive and complex Human Action has sold extraordinarily well ever since the year of its original publication.

Since Mises's death in New York City on October 10, 1973 at the age of 92, Misesian doctrine and influence has experienced a renaissance. The following year saw not only Hayek's Nobel Prize for Misesian cycle theory, but also the first of many Austrian School conferences in the United States. Books by Mises have been reprinted and collections of his articles translated and published. Courses and programs in Austrian Economics have been taught and established throughout the country.

Taking the lead in this revival of Mises and in the study and expansion of Misesian doctrine has been the Ludwig von Mises Institute, founded by Llewellyn Rockwell, Jr. in 1982 and headquartered in Auburn, Alabama. The Mises Institute publishes scholarly journals and books, and offers courses in elementary, intermediate and advanced Austrian economics, which attract increasing numbers of students and professors. Undoubtedly, the collapse of socialism and the increased attractiveness of the free market have greatly contributed to this upsurge of popularity.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995) was dean of the Austrian School after Mises's death. This piece was written circa 1990 and has never before appeared in print or online. The article is taken from the web-site www.mises.org

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________